Beautiful Plants For Your Interior

Jane M. Zhu, M.D., M.P.P., M.S.H.P., Hayden Rooke-Ley, J.D., and Erin Fuse Brown, J.D., M.P.H.

In the late 1800s, corporations began hiring U.S. physicians and profiting directly from their services without being bound by professional ethics considerations. Concerned about this commercialization of medicine, and potentially to avoid competition and tighter government regulation, the American Medical Association revised its Principles of Medical Ethics, condemning as “unprofessional” any contractual arrangement that interfered with physician practice. States soon followed by adopting the corporate-practice-of-medicine (CPOM) doctrine, which generally bars unlicensed lay entities from owning or controlling medical practices. Today, rapid corporatization of health care raises new questions about the usefulness of the CPOM doctrine: Why, despite the existence of CPOM laws in many states, has the corporate land grab in health care continued? And how can the CPOM doctrine be strengthened to protect both the medical profession and the public interest?

Although corporate ownership of physician practices is neither new nor inherently problematic, the scope of these arrangements in health care and the recent pace of acquisitions have generated attention among medical professionals, policymakers, and the public. Almost three quarters of physicians in the United States are now salaried employees, with half of all physician practices owned by a hospital or corporate entity.1 UnitedHealth Group is the country’s largest physician employer, with 70,000 salaried or affiliated physicians, and retailers such as Amazon, CVS, and Walgreens have spent billions of dollars expanding their primary care footprint in nearly every state. Private-equity investors have reached penetration rates of more than 30% in certain local markets.2 Today’s corporate investors wield greater market power and pursue more aggressive revenue models than health maintenance organizations of the past; as a result of highly leveraged and multilayered deal structures, they also tend to be more insulated from risk. Such investors provide notable benefits for practices: in an increasingly complex clinical practice environment, corporate ownership may afford much-needed capital investments, greater financial stability, improved operational efficiency and capacity, responsiveness to the implementation of alternative payment models, and an ability to scale up population health interventions.

There is growing concern, however, that corporations aren’t simply providing ancillary business and operational support but are also increasingly assuming control over clinical operations, management and staffing decisions, billing and coding practices, and negotiations with insurers — which may exert pressure on physicians to change care delivery. Emerging empirical evidence suggests three primary risks that corporatized medicine poses: increased health care prices and spending owing to market consolidation and exploitation of payment loopholes,3 patient care concerns associated with changes in practice patterns and pressures to reduce staffing, and moral injury and burnout among physicians.4 The preponderance of evidence hasn’t yet suggested commensurate improvements in quality, access, efficiency, or equity to offset these concerns.

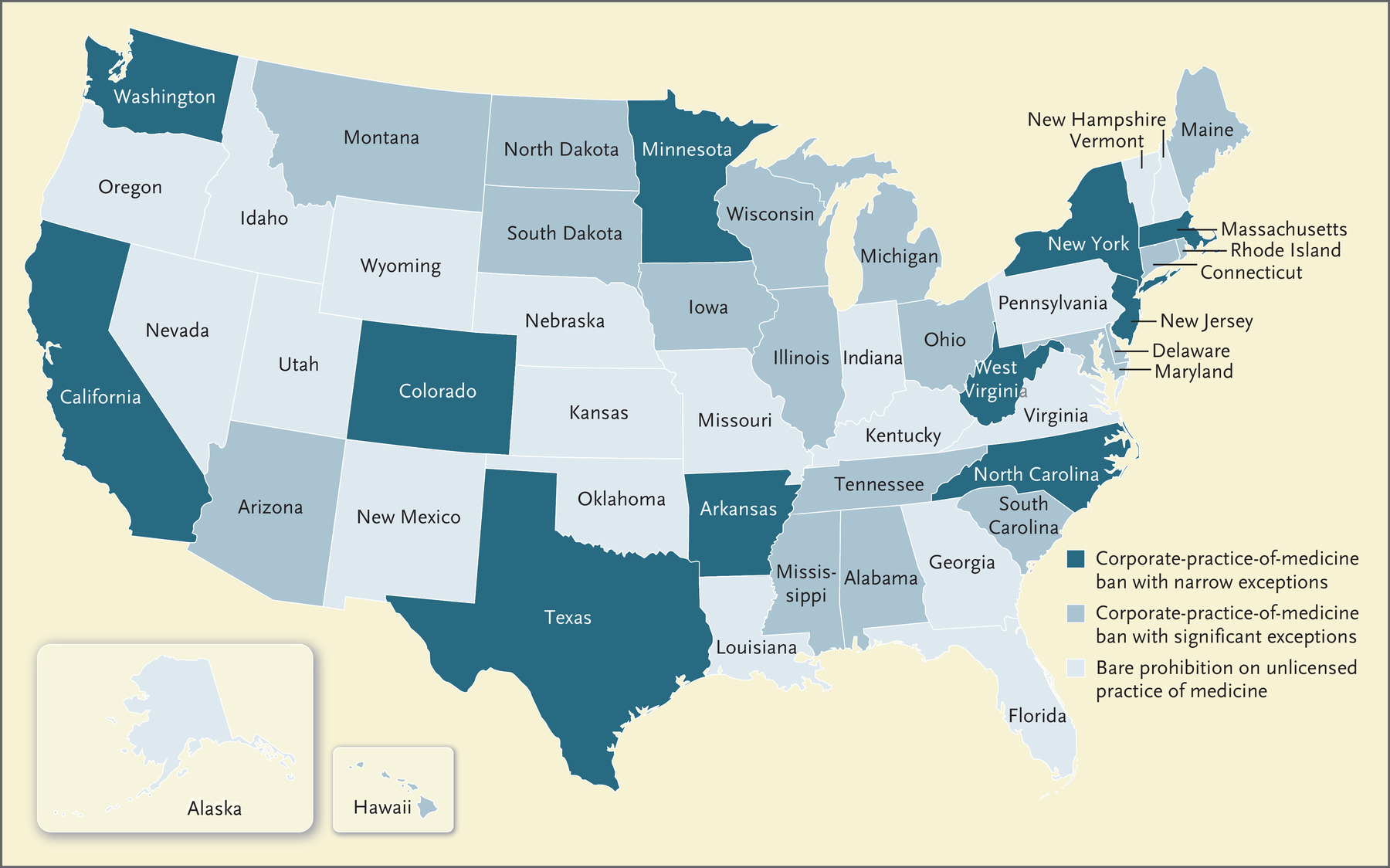

Scope of State Corporate-Practice-of-Medicine Laws in the United States.

Nationwide, state approaches to corporate medicine vary in their scope and robustness, with some states issuing no restrictions beyond a general prohibition on the unlicensed practice of medicine and others expressly prohibiting nonprofessional corporations from owning medical practices and employing physicians (see map).5 Laws in many states fall somewhere between these ends of the spectrum, typically restricting lay ownership of medical practices and employment of physicians but granting substantial exceptions, including for hospitals, nursing homes, or managed care entities — which may be reasonable in the current health care environment. Even in states with clear CPOM prohibitions, certain corporate entities, such as professional corporations (PCs), are permitted to deliver clinical services, as long as all or the majority of their owners are physicians licensed in the state. States with the strongest CPOM prohibitions (e.g., California) bar management-services companies — which provide practice-management and clinical support services to provider organizations — from exercising control or undue influence over physicians’ practice and decision making. Some states have additional restrictions on fee splitting or revenue sharing among professionals and lay entities.

Yet CPOM bans have little practical effect. There appears to be no direct correlation between the extent of corporate ownership of physician practices and the presence of clear CPOM prohibitions,2 in part because some states’ enforcement has been dormant. With the rise of managed care and integrated delivery systems, the CPOM doctrine became perceived as unnecessary and outmoded in the face of health care market innovations. A second key reason that CPOM laws haven’t prevented corporatization is the sophisticated use of management-services agreements, which allow corporate entities to circumvent corporate-practice restrictions. Under the “MSO model,” corporate entities operate a wholly owned management-services organization (MSO) that contracts with a medical practice’s PC, which although nominally owned by licensed physicians is managed and operated by the MSO. A more extreme version of this arrangement, which is prevalent among private-equity firms and other corporate investors, is the “friendly PC” model, in which a corporate investor selects a “friendly physician” to run — and often to exclusively own — the practice’s PC. Both Oak Street Health and One Medical, which were recently acquired by CVS and Amazon, respectively, use the “friendly PC” model: they appoint a medically licensed executive of their MSO as an owner, director, and officer of the target practices. Such arrangements allow lay corporations to assume de facto ownership and control of physician practices. Control is further cemented by requiring physician-owners of the PC to sign stock-restriction agreements, which prevent physicians from selling their interests or exercising certain rights in the PC without the approval of the MSO. Physician-owners are often also obligated to sign tight noncompete and nondisclosure agreements.

Even though the CPOM doctrine has become anachronistic, a renewed examination of CPOM laws may be warranted, both to adapt these policies to today’s health care environment and as a potential lever to temper the rapid pace of corporate takeovers in medicine. A 2021 California bill sought to further restrict nonphysician management and control of the clinical and business operations of physician practices but was ultimately tabled. In December 2021, the American Academy of Emergency Medicine’s physician group sued private-equity–backed Envision Healthcare, alleging that Envision violated California’s CPOM laws when it took over the staffing of a local hospital’s emergency department. The organization contends that Envision exercised a prohibited level of control over the physician group by means of stock-transfer agreements and oversight of staffing, physician compensation and work schedules, coding decisions, payer contracts, and performance standards. This case, which is still pending, could set a precedent for invoking the CPOM doctrine against contemporary corporate-ownership arrangements.

States seeking to counter the corporatization of medicine could strengthen their CPOM laws in several ways. First, they could close existing loopholes that permit corporate ownership. For example, although Oregon has physician-ownership requirements for PCs, limited-liability companies and partnerships can deliver medical services in the state without being subject to such requirements.

Second, states could regulate the MSO model. As proposed in California, states could require that PCs retain “ultimate control” over both clinical and business decisions and require maintenance of physician board seats and equity in the practice when there are ownership changes. States concerned about “friendly PCs” could go a step further and exclude people from serving as shareholders, directors, or officers of both an MSO and a practice operated by the MSO. In other words, a PC wouldn’t be able to claim to meet the requirement of ultimate control by licensed professionals if such professionals were also representatives of the MSO.

Third, states could loosen the grip that corporate investors can have on clinical practices by barring physician contracts from including restrictive provisions — namely stock-restriction agreements, noncompete clauses, and gag clauses — and protecting whistleblowers from retaliation when they raise patient-safety or ethical concerns. Finally, broader enforcement is needed if CPOM restrictions are to have meaningful effects.

In the current wave of health care corporatization, the original need for the CPOM doctrine has resurfaced. If sharpened, honed, and enforced, CPOM laws could be useful guardrails to ensure that physicians’ clinical decisions and professional autonomy aren’t superseded by corporate pressures.

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available at NEJM.org.

This article was published on September 9, 2023, at NEJM.org.

Author Affiliations

From the Division of General Internal Medicine, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland (J.M.Z.); Stanford Law School, Palo Alto, CA (H.R.-L.); and the Center for Law, Health, and Society, Georgia State University College of Law, Atlanta (E.F.B.).

Supplementary Material

| Disclosure Forms | 414KB |