Beautiful Plants For Your Interior

Rachel Morello-Frosch, Ph.D., M.P.H., and Osagie K. Obasogie, Ph.D., J.D.

Driven primarily by fossil-fuel use and associated carbon emissions, climate change poses an existential threat to planetary life by transforming physical and social environments through rising sea levels, drought, heat waves, more intense hurricanes and flooding, and disruptions to energy and food production.1 Current and projected health, environmental, and socioeconomic effects of climate change are well-documented and central to environmental justice because of their disparate effects on marginalized populations. Debates about disparities in the effects of climate change have traditionally focused on their global dimensions — in particular, how formerly colonized countries that are least responsible for greenhouse-gas emissions are the most threatened by the multiple risks of global warming and lack the resources to resist the forces of climate change and survive.2

The Climate Gap

Within the United States, climate change and fossil fuel–generated air pollution have disproportionately harmed people of color and low-income communities, which is also true of some strategies to mitigate climate change.3 These inequitable effects on racially marginalized groups have been described as the “climate gap”4 and have led to mounting calls for policymakers to address the “syndemic” (or synergistic epidemic in which multiple factors create or worsen a health crisis) of climate change, economic injustice, and the enduring legacies of slavery, Jim Crow, and resulting forms of structural racism that largely segregates society — what sociologist W.E.B. DuBois described in the early 20th century as “the color line.” It is critical to protect communities that are most vulnerable to rapidly changing climate conditions and have the fewest resources to prepare for and recover from extreme weather events and other climate-related hazards (i.e., communities of color, Indigenous peoples, and low-income communities). Vulnerability to climate change is determined according to the ability of communities and households to anticipate, avoid, mitigate, and recover from the direct and indirect effects of climate change, including extreme weather events, geophysical shifts, and infectious diseases. Collectively, these scenarios indicate that climate change will amplify existing health, social, and economic inequalities while creating new ones.

Structural Drivers of Climate Change and Health Inequities

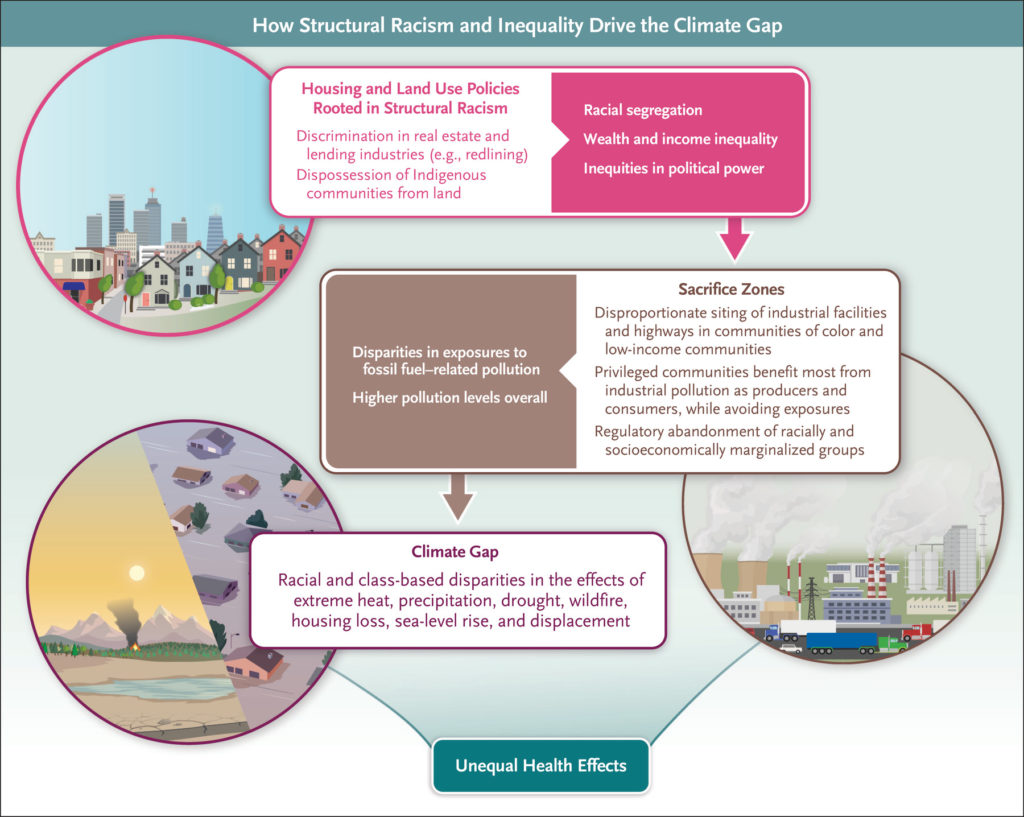

Figure 1.

How Structural Racism and Inequality Drive the Climate Gap.

Greenhouse-gas emissions that cause climate change are driven in part by systemic inequalities, including large disparities in wealth and political power, as well as racial and ethnic segregation (Figure 1).5,6 To be effective, climate-change mitigation and adaptation strategies must address these structural factors. Research has shown that societies with social and economic inequities may be more likely to pollute or otherwise degrade their environments.6 The economic benefits that result from polluting activities are accrued more by wealthy persons, both as producers (e.g., shareholders of polluting industries) and consumers (since consumption increases with wealth), than by low-income persons. Wealthy persons avoid the harmful effects of pollution by, for example, moving away from industrial areas or wielding political influence to keep polluting activities away from their neighborhoods. This physical separation between privileged and disadvantaged communities can solidify and amplify patterns of racial residential segregation that have been associated with higher levels of traffic-related air pollution that also disproportionately affect communities of color.7,8

Legacies of structural racism have resulted in “sacrifice zones” where the inequitable distribution of pollution sources,9 including major roadways, rail lines, ports, and industrial facilities, have led to disproportionate air pollution exposures borne by communities of color and low-income communities.10 For example, the federal Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, in trying to revive the housing market in the 1930s in the wake of the Great Depression, conducted “redlining” by grading and mapping neighborhoods in cities across the United States according to perceptions of risk in real-estate investment.11 These risk criteria were often racist, in which neighborhoods composed of largely low-income, immigrant, or Black residents were deemed to be “hazardous” or “definitely declining” and mapped in red (i.e., redlined), whereas wealthier communities with more White residents were considered to be the “best” or “still desirable.” Historians have shown that these maps reflected racism perpetuated by government and private actors within urban real-estate markets beginning early in the 20th century.12 Discriminatory lending and systematic public disinvestment in formerly redlined neighborhoods, followed by discriminatory Federal Housing Authority policies,13 have contributed to the destruction of many Black communities through their bifurcation by highway construction14 and urban renewal programs.15 Today, many of these neighborhoods have worse air quality,8 minimal green space, and higher risks of heat-island effects,16 as well as elevated rates of cardiovascular disease,17 hospitalizations for asthma,18 poor birth outcomes,19 and other diseases,20 thereby increasing vulnerability to the adverse health effects associated with climate change.

Pathways Leading to Inequitable Harms

There are multiple pathways through which the extraction and combustion of fossil fuels and associated climate-change effects disproportionately harm communities of color. We discuss key examples below.

FOSSIL-FUEL RISKSCAPES

Many components of the fossil-fuel supply chain and infrastructure in the United States are disproportionately located in communities of color and low-income neighborhoods, thereby creating inequitable landscapes of environmental health risk, or “riskscapes,” that include pipelines and refineries,21 ports,22 and upstream oil- and gas-extraction sites.23 Historically redlined neighborhoods have nearly twice the density of oil and gas wells than otherwise similar neighborhoods that were not redlined.24 Drilling and operating oil and gas wells worsen air pollution25 and are associated with increased risks of health problems, such as respiratory disease,26 cardiovascular disease,27 depression,28 and poor birth outcomes29 (including premature birth30), among residents living nearby; these health risks are often greater in marginalized groups. Moreover, in areas where communities of color and Indigenous groups have resisted the construction of hazardous fossil-fuel infrastructure, reports have shown that the fossil-fuel industry has provided funding to police to support the purchase of weapons, surveillance, and violent suppression of protesters.31

SEA-LEVEL RISE, FLOODING, AND EXTREME STORMS

The frequency and extent of flooding are increasing because of sea-level rise, more frequent storms, and heavy precipitation events, which have implications for health equity.32 The flooding associated with Hurricanes Katrina, Harvey, Sandy, and Maria disproportionately affected people of color and low-income people who were more likely to live in flood-prone zones33 and have a greater risk of injury or death, as well as mental health conditions (e.g., anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder) that are associated with such disasters.34 Persons living in these communities are less likely to have access to cars for evacuation, have adequate home insurance, or be able to return and rebuild afterward.35 Institutionalized groups, including prison populations (in which people of color are disproportionately represented), have faced life-threatening experiences during extreme storm events.36 Major drought, flooding, and precipitation also compromise critical infrastructure, such as wastewater treatment,37 community drinking-water systems, and domestic wells.38 Communities of color and low-income populations are more likely to be exposed to unsafe drinking-water quality and degraded sanitation infrastructure,39 which increases their vulnerability to major storms. Such susceptibility was most recently evidenced by the collapse of the drinking water supply in Jackson, Mississippi, where nearly 150,000 predominantly Black residents were left without access to safe drinking water because of torrential rains and decades of disinvestment.40

Extreme storms and sea-level rise also threaten chemical and other manufacturing plants, power plants, hazardous-waste treatment facilities, landfills, and legacy clean-up sites that store, use, or emit hazardous materials, leading to natural–technological disasters (i.e., cascading events in which floods or extreme winds trigger releases of hazardous materials in communities living nearby). In major hurricanes, releases of toxic chemicals into local air and floodwaters have occurred accidentally or intentionally (e.g., to prevent explosions).41 Across the United States, low-income people and people of color are more likely to live near hazardous-waste and industrial facilities.42 Thus, during extreme storms, coastal flooding of contaminated and hazardous sites has disproportionately affected socially disadvantaged populations.43 Studies that project future sea-level rise and flooding scenarios in low-lying coastal areas suggest that many communities, particularly those close to legacy clean-up sites, will experience more frequent and destructive flooding in the years ahead.44

Sea-level rise is imposing displacement pressures on communities of color, including tribal populations that are being forced to relocate inland, away from low-lying areas, in places such as Alaska, Washington, and regions along the Gulf Coast.45 Flooding also poses substantial threats to existing affordable housing stock, particularly in the Northeast.46 In Florida, sea-level rise is creating new gentrification pressures, as wealthier coastal inhabitants seek to move inland to neighborhoods that are at a higher elevation.47

EXTREME HEAT

High temperatures are associated with higher risks of illness (e.g., adverse cardiovascular, mental health, and pregnancy-related outcomes) and death among adults of color than among their White counterparts.48 In addition, the prevalence and severity of preterm birth is likely to worsen with increasing temperatures and exacerbate racial disparities in preterm birth rates.49

The greater vulnerability of communities of color and low-income communities to heat is explained by inequalities in neighborhood-level exposures to extreme temperatures, workplace conditions, housing quality, access to air conditioning, prevalence of underlying chronic health conditions, and other effects of structural racism and socioeconomic marginalization.50 These groups more commonly experience urban “heat-island” effects, owing to the lack of tree canopy and prevalence of impervious surfaces, such as roads and sidewalks, that decrease the dissipation of heat and increase warming. A national analysis showed higher rates of land-cover patterns associated with greater heat-related risks in neighborhoods housing Black, Asian, and Hispanic persons than in predominantly non-Hispanic White neighborhoods.16 Lack of access to air conditioning and other cooling technologies is also common in communities of color and low-income communities, particularly among older adults and disabled persons residing in urban areas, which predisposes them to heat-related health complications and death. One analysis of weather data from Chicago, Detroit, Minneapolis, and Pittsburgh showed that Black persons had a 5.3% higher heat-related mortality than White persons and that almost two thirds of this difference was potentially explained by racial disparities in access to central air conditioning.51 Latinx workers are disproportionately represented in hazardous outdoor occupations, including agriculture, landscaping, and construction, in which the risks of heat-related health complications and death are highest.50,52

WILDFIRES

Wildfires are increasingly fueled by climate change, and exposures to wildfire smoke pose considerable health risks to affected populations. Incomplete combustion during wildfires generates not only fine particulate matter (particles with an aerodynamic diameter of ≤2.5 μm [PM2.5]) but also nitrogen dioxide, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, volatile organic compounds, and trace metals. These particles can travel long distances,53 potentially harming communities hundreds of kilometers away from the wildfire.54 Although environmental regulations have led to a decrease in PM2.5 levels in the United States, wildfire-related PM2.5 levels have increased, particularly in the western states.55 Communities of color face a high risk of wildfire hazards and, along with low-income populations, may have elevated exposures and risks of adverse health effects, including cardiovascular and respiratory events, associated with wildfire events and smoke. These elevated exposures are due to higher rates of outdoor work (e.g., agricultural and construction sectors) and occupancy in poor-quality housing (where wildfire-related air pollutants can penetrate indoor environments). In addition, such communities have limited ability to evacuate, a high prevalence of existing respiratory and cardiovascular conditions, and barriers to health care access.56 People of color are also at higher risk for wildfire-related cardiovascular and respiratory events than White persons.57

Closing the Climate Gap

Proactively alleviating the climate gap requires action across multiple pathways. Multipronged strategies involving physicians and public health practitioners can motivate the policy changes that are needed to advance sustainability and environmental justice goals.

When caring for patients and educating communities about the health risks of climate change, physicians and public health practitioners need to understand and emphasize the structural determinants of these health challenges. Embedding this form of structural competency58 in medical education and public health curricula can help ensure that health providers recognize that the health threats caused by climate change cannot simply be addressed at the individual level but require systemic transformations of our energy, food-production, economic, legal, and health care systems.

In addition, physicians can do more to collectively advocate for systemic change that puts environmental justice and health equity at the center of addressing the climate crisis at the local, state, and federal levels. This strategy presents opportunities for health care professionals to partner with and follow the lead of community-based organizations and nongovernmental groups to advocate for policies that integrate decarbonization efforts with broader programs of social, economic, and democratic change that address inequity and help close the climate gap. Examples of such policies include ensuring access to thermally efficient and gas-free public housing and schools, zero-emission and nonpolluting household energy and public transportation, safe and affordable drinking water, and sustainably produced and nutritious food, as well as opportunities for workforce development related to climate, sustainability, clean energy, housing, and other infrastructure initiatives. Linking decarbonization with economic programs, such as affordable housing, higher wages, and educational and job opportunities, elevates public support for climate-change mitigation, particularly in communities of color.59

Such holistic climate policies can explicitly lay the groundwork for connecting climate-change mitigation and adaptation with community building, economic opportunity, and political power in ways that advance racial and economic justice and reduce health inequities. The Justice40 Initiative, developed by the Biden administration, signifies a bold step in this direction by requiring that at least 40% of investments from federal programs in clean energy, transit, affordable and sustainable housing, workforce development, remediation and reduction of legacy pollution, and clean water and wastewater infrastructure benefit “environmental justice communities” (i.e., marginalized and disadvantaged communities that are disproportionately affected by multiple environmental hazards). This work has been bolstered by the passage in August 2022 of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which provides historically unprecedented investments to address climate change and amends the Clean Air Act to include six greenhouse gases as air pollutants, thus strengthening authority of the Environmental Protection Agency to address climate change in several programs. Although the IRA contains problematic elements (including provisions that could increase fossil-fuel production and subsidies for hazardous industries that deploy carbon capture, storage, and utilization technologies), the legislation has the potential to be a transformative step toward closing the climate gap. It includes substantial federal support to reduce historic sources of pollution in overburdened communities, provides affordable and accessible sources of clean energy, and rebuilds critical infrastructure.60 Community- and data-driven accountability structures that track the socioeconomic and health effects of these investments is critical to hasten the U.S. energy transition in ways that advance health equity. Ultimately, effective policies to address the climate gap must prioritize the needs and elevate the leadership of environmental justice communities that continue to endure the disproportionate health burdens of climate change and our extractive fossil-fuel economy.

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

Author Affiliations

From the Department of Environmental Science, Policy, and Management and the Divisions of Environmental Health Sciences and Community Health Sciences, School of Public Health (R.M.-F.), and the School of Law and Joint Medical Program, School of Public Health (O.K.O.), University of California, Berkeley.

Supplementary Material

| Disclosure Forms | 155KB |